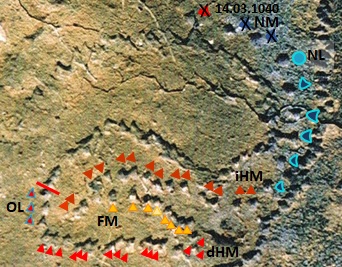

…….On the Canary island La Palma there are above all in the municipality of Garafía numerous petroglyphs. From a group of artificially arranged stones, >El Calvario<, one rock engraving (photo N° 2) struck me. Above the motive shone the deep blue sea, but, if we turned around, we could see to the right of the white cemetery and in some distance a remarkable mountain which apparently had two peaks (photo N° 1). After several years, when we knew for certain how to decipher some other carvings, we gave the information to suitable people and then we returned to examine this region more closely.

Photo N° 2 The sketch of the rock engraving in a topographic map and a photo of the real carving on the rock.

According to the biggest engraving the Montaña de Fernando Porto has a plain, wide and almost circular surface at the southwestern “peak” (photo N ° 3), while its northeastern part is narrow and long, so that nowadays there is just enough room for a road (photo N° 4).

Photo N° 3: View from the higher top of the Montaña de Fernando Porto at its round and lower half.Photo N° 4: The nearly oval and raised part of the mountain.

Photo N° 4: The nearly oval and raised part of the mountain.

Photo N° 5: View from the Montaña de Fernando Porto in direction straight up.Photo N° 6: The inconspicuous Montaña de Las Indias.

In photo N° 5 we look from Montaña de Fernando Porto up the slope, where the pyramidal contour of the Montaña Cruzada dominates, which has, however, to the east an elongaled, oval base. From the Montaña de Las Indias, which is nearly circular, one just can make out the small peak (red mark), but only if one knows where to look!

Further up we reach Llano Negro. From this plain the small mountain can hardly be seen, either, because it almost disappears in the trees (photo N° 6). When we are finally standing at the summit of the Montaña de Las Indias, it seems to be artificially flattened. On its round and red surface, ancient people could have lit fires to transmit news to people on the Montaña de Fernando Porto and on the edge of the Caledera de Taburiente (photo N° 7).

Photo N° 6: The inconspicuous Montaña de Las Indias.

Photo N° 7: The pulled down or leveled summit of the Montaña de Las Indias.

In photo N° 8 the right arrow points to the Barranco de La Luz.

Beneath the middle arrow, we can see the high mountain zone with the highest peak of the island, the Roque de los Muchachos. These visible slopes of the so-called cumbre, belong to the large pastures which were used by all the shepherds during the summer in a communal manner. The arrow on the left points to Lomo Mataburras.

Photo N° 8: View from the Montaña de Las Indias in the direction of the cumbre.

Photo N° 9 with a view from the top of the Montaña de Las Indias shows the minute, barely visible double peak of the Montaña de Fernando Porto (photo N° 10, red marked area). This depicts the farthest possible distance from which one could send a beacon from the cumbre to the coastal area – by means of two fireplaces!

Photo N° 9: View from the Montaña de Las Indias in the direction to the sea; on the right sight is the long Montaña Cruzada.

Photo N° 10: The higher, back side of the double top of the Montaña de Fernando Porto.Photo N° 9: View from the Montaña de Las Indias in the direction to the sea; on the right sight is the long Montaña Cruzada.

……If we follow the footpath, which branches off on the right just behind the Montaña de Las Indias, it runs down into a barranco, through which even today a shepherdess leads her goats. As soon as this path reaches the bottom of the valley, due to the density of the shrubs, we can hardly make out the modern spring at the foot of a rock slope (photo N ° 11; with exposed detail).

The meadows below the Fuente de Oropesa are very humid in wintertime.

Could it be, that there is still a hidden and undiscovered engraving beneath the thicket of pine needles and plants?

Photo N° 11: The Fuente de Oropesa, below three pines and a lot of bushes.

…….In the Barranco de Jerónimo, the Fuente del Colmenero has quite a different character. As water flows all year and with bigger quantity. It was already known to the natives because we can find engravings which they had made in the rocks (Photo N° 12).

Photo N° 12: The Fuente del Colmenero, which is sheltered by stone walls and a wood roof. Engraved symbols of a spiral which runs out into a kind of meander can be seen on the rocks above the spring.

…….However, what is the real connection between the carving on the stone of >El Calvario< and the afore-mentioned mountains and springs? Possibly the petroglyphs show the main settlement and travelling area of some families who lived in the surroundings of the Barranco de Fernando Porto.

In Garafía there are high cliffs and this means that people can only reach the sea in the mouths of the barrancos. The town of Santo Domingo is situated directly on the boarder of the Barranco de La Luz. But this canyon doesn’t end in a real bay. Therefore the harbour was built farther to the south, at the mouth of the Barranco de Fernando Porto. This bay is protected by two spits and, besides, large striking rocks are still offshore, so that there are protected areas, in which people can bathe or collect mussels and catch fish.

…….Higher up, about 200 to 400 metres, only gradual wide slopes can be found with spurge plants (Tabaibalvegetation) and also many forage crops, so even today in this region big herds of goats roam around. In this open and windy area, there are some ancient stone arrangements with quite different engravings. For example, close to Santo Domingo is the archaeological site >El Calvario< and nearby the Barranco de Fernando Porto is situated, below the cemetery, >El Calvario<. Moreover, there are there still many other findings of different significance and interesting individual objects. This vegetation zone is narrow, because the area soon rises steeply.

…….„The Awara lived as semi-residential herdsmen and the cattle were of the greatest, beside fishing, hunting and agriculture. In temporal as well as spatial terms the short distances travelled are very similar to the system of the nomadic economy, the transhumance. Only the shepherd with his cattle goes on his circular journeys (from the coast to the summits), while women and children always stay in the permanent settlements. Groups of 2 – 5 families keep herds of more than 400 animals (goats, sheep and pigs) whose number depends, however, on environmental conditions and the means available. …“ (Martín González, 2007; [1]).

…….In the next vegetation zone the Montaña de Fernando Porto is the most prominent elevation. On its south-western side runs a barranco with the same name and from there we can see some caves on the mountain side. The gulch is wide, small fertile terraces pass through it and there we also found a round rock which had been hewn in a wonderful way to collect rainwater. Above the Montaña Cruzada the Barranco de Fernando Porto is joined by the Barranco de Oropesa, in which, near the Montaña de Las Indias, the Fuente de Oropesa rises. Both barrancos, Fernando Porto and Oropesa, start on about the same level and relatively close together, above the small village of Hoya Grande and south of the settlement of El Bailadero.

…….Farther east, there is a circular place on the slope which is surrounded by several especially tall pines. Unfortunately, a big water tank was built directly above it, so presumably the upper part was destroyed. Photo N° 13 shows the view from that spot. On both sides you can see the pines which frame the scene around the Montaña de Las Indias (red arrow). On the left of the mountain runs the shady canyon with the Fuente de Oropesa and then comes the settlement of Hoya Grande.

Photo N° 13: Lugar por encima de Hoya Grande, después de las primeras curvas de la carretera que lleva al Roque de Los Muchachos.

…….The magic site could have been a cult place, a baladero, from which the calls of the people and animals resounded far away: „If there was a need for water, and they had some needs, they took the sheep and goats and with them everybody, men and women and children, gathered at certain places; and there all the people raised their voices and the cattle bleated, around a pole which was put into the ground where they remained without eating, until it rained … (friar Abreu Galindo, XVI century).“

…….It strikes you that above both springs there are very old pines. And from another spring, the Fuente del Pino, big pines line the path through the Barranco de La Luz up to the place, from which one must climb up to the biggest pine, in order to reach the baladero. Is it possible, that big trees were marking points for shepherds from other regions?

…….At this altitude, between 800 and 1200 metres, the upper part is fairly plain and just covered with low vegetation. In comparison with the barrancos, which are almost totally covered with Fayal-Brezal-societies and with lichens, light can hardly reach the ground. From November till approximately June, this zone is relatively humid and there are numerous springs, so that the shepherds with their mixed flocks will find enough food.

…….„In summer when the sun has scorched the pastures along the coasts and in the middle zones, they move to the summits where communal farming is done, which are confined limit by the external outline of the Caldera de Taburiente, at 1.700 – 1.800 metres, where the camps of the shepherds increase and the inner walls of the big crater are to be found“ (Martín González, 2007; [2]).

…….Above Hoya Grande the street meanders to the highest point of the island. I suppose that the natives went straight up through the pine zone on this ridge to reach the cumbre. Because of the form of the relief, this region is the most extensive pastureland in the northern high mountains, which could have been used communally by the natives. Here the shepherds just had small huts and shelters in which they could also produce and store cheese, and where they probably stayed till December, in many a dry year. Numerous rock engravings and archaeological objects from all ages were found there. South of there, but close to the cumbre, two big Barrancos de Briestas and Izcagua begin and between them ritual heaps of stones were discovered, so-called amontonamientos: >Las Lajitas< and the marks at Cabeceras de Izcagua. If we look in a straight line over the stone heaps at certain natural, striking elevations, the solstices and equinoxes were to be observed in these directions and the annual cycle could be divided with precision (more about: http://prehistorialapalma.blogspot.de/2009/03/plinio-junonia-mayor-y-el-templo-de.html).

…….So let’s look once again at photo N° 2. The carvings on the rock show not only the two circular elements >Montaña de Fernando Porto< and >Montaña de Las Indias< with the spiral >Fuente de Oropesa< virtually together, but slightly below we can see another spiral and a circle. The position of the Fuente del Colmenero could more or less fit the arrangement of the petroglyphs. So if we follow the Barranco de Atajo from the sea, the Barranco de Jerónimo with the Fuente del Colmenero enters and it runs directly along the southern side of the ridge with the baladero and the road to the Roque de Los Muchachos, as far as the dwelling houses of the astrophysical observatory. The upper part of the barranco also belongs to the region that we have described before.

…….As for the small circle-symbol, the conjecture is even more vague than in the case of the spirals in relation to the numerous springs. This sign consists of only one circle, so it could symbolise a round place which is connected to other fire places at the greatest possible distance, too.

Photo Nª 14: Era or tagoror? La Padona, 16.06.2008.

Spontaneously I remembered that in the south of the Fuente del Colmenero a perfect, very big and plain ledge which is situated near the road to El Castillo, on the left of the Barranco de Fuente Grande. This region is called La Padona and the panorama is wonderful, which might be a reason for the place being enclosed with stones. I’m not sure whether it was an era / a place for trashing the corn, a tagoror / a meeting point of the former headmen or even an observation place to determine the solstices and equinoxes by the sun sets, but this can be still examined. However, the view is blocked by pines.

On the north of this ledge there is a pylon with high voltage transmission line, which leads straight ahead to a level directly above the Fuente del Colmenero. Could it be that the ledge La Padona and the area above the spring were important for fire signs, too?

…….If we really have properly deciphered the mountains and springs of the petroglyphs, the Montaña de Fernando Porto could depict a settlement area. The region between the Barranco de La Luz and the Barranco del Atajo / Jerónimo could show a “private” area with cattle breeding, springs and probably also some agriculture. Presumably, the main path led from the mouth of Barranco de Fernando Porto up to the Roque de Los Muchachos. The fact that this pretty straight line, besides the Montaña de Fernando Porto, shows the insignificant Montaña de Las Indias, can be explained only by the visibility, which however, on account of the distance, could only have had a meaning with the help of fire signs at night, smoke or even acoustic signals during the daytime. The fires could indicate cattle theft and other dangers, as well as rituals, celebrations or plays; or they could summon the community or just the chiefs in the event of any conflicts …

[1] Martín González, Miguel Ángel. http://prehistorialapalma.blogspot.com/2007/11/el-rgimen-de-propiedad-comunal-entre.html

[2] dito

This article was published on the 6th of March, 2015 in the IRUENE N° 6, a magazine of the Archeoastronomer Miguel Ángel Martín González: https://elapuron.com/noticias/municipios/14729/el-sexto-nmero-de-la-revista-iruene-aborda-los-enigmas-de-las-estaciones-rupestres-de-el-bejenao/

This article was published on the 6th of March, 2015 in the IRUENE N° 6, a magazine of the Archeoastronomer Miguel Ángel Martín González: https://elapuron.com/noticias/municipios/14729/el-sexto-nmero-de-la-revista-iruene-aborda-los-enigmas-de-las-estaciones-rupestres-de-el-bejenao/

IRUENE – La Historia Antigua de la isla de la Palma. Miguel Ángel Martín González. Asociación Iruene La Palma.

See also: This rock engraving shows perhaps the Montaña de Fernando Porto

See also: This rock engraving shows perhaps the Montaña de Fernando Porto

This article was published on the 6th of March, 2015 in the IRUENE N° 6, a magazine of the Archeoastronomer Miguel Ángel Martín González:

This article was published on the 6th of March, 2015 in the IRUENE N° 6, a magazine of the Archeoastronomer Miguel Ángel Martín González: